The first bite of a large (economic) digestion

How is the "richness" of a country measured? And what influences it?

Disclaimer: I am not an expert on anything. Take everything you read here with a grain of salt, comment on any questions you have, point to any mistakes I write, and, before quoting me, check the sources at the end. This is more of a dialogue between you and me, and between me and myself, than an authority you should quote from.

Michel Lotito had a weird diet. At the age of nine, he began eating glass and metal which lead, some years later, to the impressive feat of eating a "low-calorie" Cessna light aircraft. Yes, you read that right: an aircraft. [1]

He of course did not boil the whole aeroplane one day and ate it all at once. He chewed a piece of the wing here, a chunk of the motor there, and after two years, he had finished it.

How Mr Lotito is an example to me

After my last post, Daniel Correal gave me Descrifrar el futuro (thanks again 😁). It is a book by Fedesarrollo, a Colombian think tank that points to the biggest challenges that Colombia faces today and possible solutions to them.

I just have a small problem: the book is rather thought for someone with a bit of a background in economics. This means that, just like Mr Lotito, I have to (metaphorically) chew very small chunks of the book at a time. This post is the first such chunk.

Why are some countries rich while others are poor?

My family took me to Disney World in Orlando when I was a kid. I was afraid of rollercoasters (and still am 🙃). But seeing the contrast between the US and Colombia really struck me. I remember wondering: why are some countries rich, while others are poor?

This is a very big question, and many economists spend lifetimes researching it. This post will not answer that question. But it will lay some ground to start looking at it in future issues.

First: what do I mean by a rich country?

When I think of a rich country I think about a place where high-quality education is free for everyone, water is drinkable everywhere, moving from A to B is easy and fast, everyone can be treated by a good doctor, etc.

These characteristics can be achieved with money. So I am focusing in this post on measuring that money in a country. Just a small disclaimer before diving in: a lot of money does not directly mean high standards of living. [2] For example a country that produces a lot, could have a small portion of the population profiting most from that production, leaving the rest of the population with lower standards of living. But this is a big topic that I will treat in more detail in a future post.

Measuring money

Let me start by throwing a definition

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the world’s most used statistical indicator of national development and progress. [3, 4] It tells us how much a country produces inside its borders. Divide that GDP by the total population and you get the GDP per capita, which measures the average economic output of every citizen. [5]

I read the definition of GDP multiple times. But only after looking at examples, I felt I had understood it. For this reason, let me explain the above definition with the example of Auroria, a fictitious country famous for its delicious apples. [6]

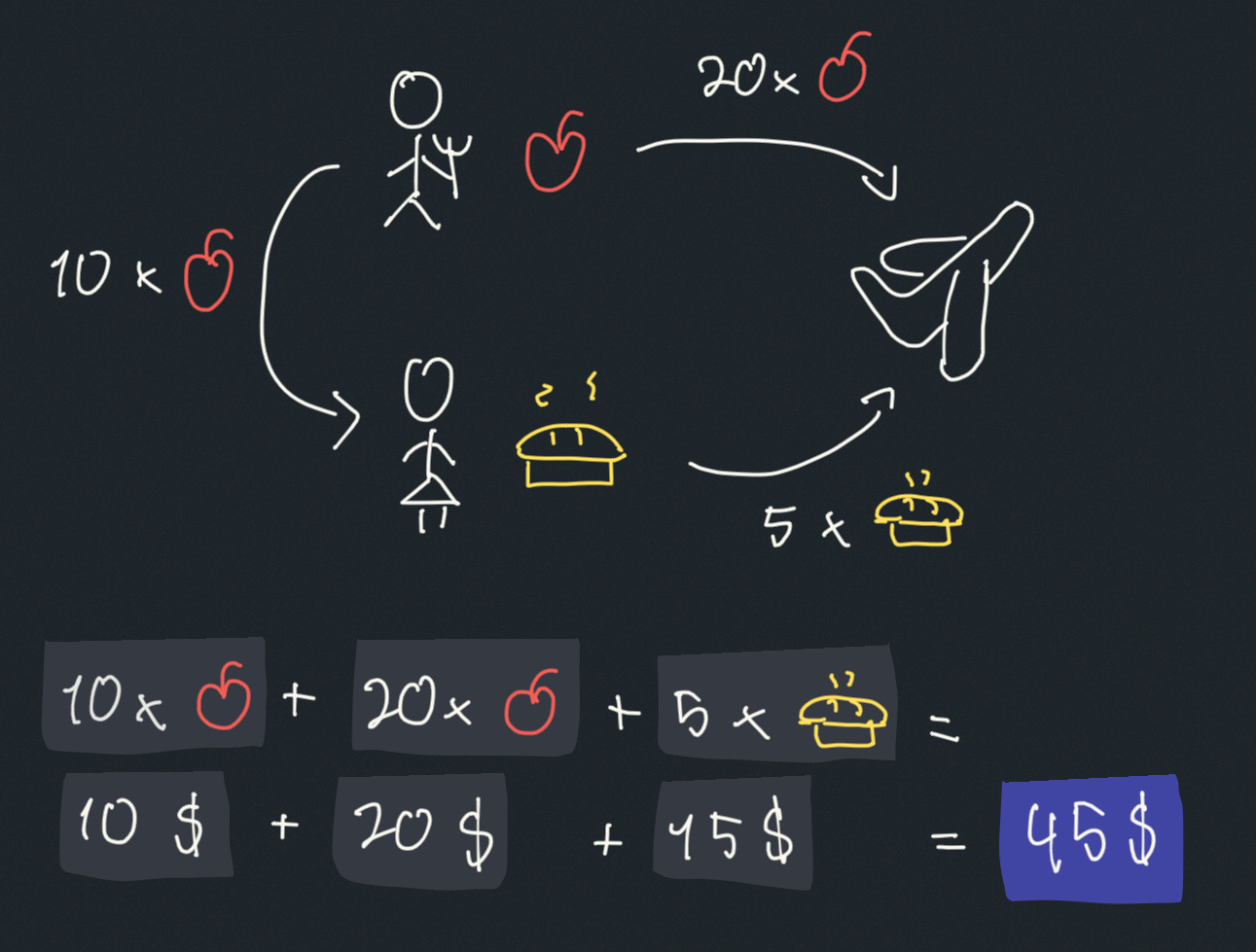

In Auroria there are 5 people. Three are apple farmers and two make apple pies. The apple pie makers buy from the apple farmers. Both the farmers and pie makers export their produce. One apple costs 1$, one apple pie 3$.

The apple farmers export 20 apples and sell 10 to the apple pie makers, so that these can export five pies. The GDP of Auriria is then the 20 exported apples times 1$, the 10 apples for pies times 1$ and the 5 pies times 3$, totalling 45$. The GDP per capita would total 9$.

Here is a short image to clarify that (sorry, part of the reason I studied computer science is that my motor skills did not allow anything artsy)

Measuring growth

Auroria's economic output is 45$. By tracking it over time, we can review the economic growth of the country. If the output grows in a year, it usually means that the citizens of Auroria are doing better in that year than in the last. If the output falls, it means that they are doing worse. This principle is known as the growth imperative [7], and economic growth is even part of goal nr. 8 of the UN's sustainable development goals [8]. The theory has its controversies, but those are a topic for another time.

To summarise this first section: A country's economy is measured through its production. And the economy should grow every year.

Trying to make GDP grow

Imagine you are elected as the president of Auroria and are tasked with increasing its GDP.

You have several options. Here are a few:

1. Force all citizens to work more hours.

2. Invest in an apple-collecting machine which increases apple production

3. Train one of the apple farmers to make apple pies.

4. Download an app on the farmer's phones that helps them add fertilizer at the right times, increasing apple production.

I am sure you can think of more options. And I am going to use that to promote the subscriber chat feature of this newsletter. If you haven't downloaded the substack app, I would recommend you to do so and join the conversation. You can use it to suggest corrections, ask questions, recommend readings, and of course: share ideas to increase Auroria's GDP. 👇

Ok enough advertising, back to the options: [9]

Increasing the number of hours, besides making you a ruthless leader, would make farmers and apple pie makers work harder and result in more apples/pies being made. (This is a simplification, working a field more doesn't mean that apples grow faster but let's say that is the case for Auroria).

Investing in the apple-collecting machine would be investing in the country's capital. Capital is defined as the things used to produce other things. [10] By increasing the country's capital, you increase its productivity.

Investing in the training for apple farmers would be investing in your country's human capital. Human capital refers to the knowledge, skills, and experience (among others) that make people more productive. [11]

The last option increases the productivity of farmers without a price in either capital, as farmers already have phones, or work hours. It just makes the time of farmers more efficient.

We can put the above relations into a formula:

The formula above is the Cobb-Douglas Production Function. [12, 13] In it:

Y represents total production. That would be the GDP.

L stands for labour. That would be person-hours worked in a year.

K stands for capital. It measures all machinery, equipment and buildings.

A stands for Total Factor Productivity (TFP) - an index that points to the change in output (GDP) that is not explained by a change in either labour or capital. [14]

Beta and Alpha are constants. They are not relevant for this post.

Productivity

In the above formula I find the A most interesting. It points to the productivity of the country. In 1980, the average worker in the US produced 2.7 times more than the average worker in Colombia. Today, the same ratio has grown to 4 [15].

I want to understand that better. Why does the average worker in one country produce more than the average worker in another one? Why does the productivity grow more in one place than in another? What can countries such as Colombia do to make its workers more productive? I will start to discuss this in my next issue. If you haven’t, you can subscribe below to continue to be part of the conversation.

To sum up this section: For the GDP of a country to grow, its capital (things to produce other things), the amount of worked time in the country, or the productivity must increase.

Enough facts

So far, I have presented you with economic facts: GDP measures the economy of a country, it should grow, and to do so, either capital, work hours or productivity must increase.

Writing about that has helped me to better understand economic relations. I have the feeling economic is very full of jargon and now, thanks to writing this, I am a bit closer to understanding what all that mumble-jumble means.

But most importantly, it has raised more questions which I will be exploring in next chapters. If you have any resources that might help, or different questions that this post has raised, please share them (on the substack chat, by commenting, or by answering this email). As I mentioned at the very beginning: this newsletter is a conversation. And you are a key part of it.

Open questions

Here is a list of some of the questions I will be reviewing in later issues.

How can the productivity of a country be increased? What variables affect productivity (The A in the Cobb-douglas production function)?

Why is GDP the most used index in economics? How and when did it become so relevant?

What does GDP (growth) not tell us? What indices measure quality of life more efficiently? And why don't we use them more than GDP?

Why I am doing this

As a closing note, I think it is relevant to repeat why I wrote this issue and plan to write more.

I am currently founding an EdTech startup in Colombia, a country that is developing and faces many challenges. Currently, I want to better understand these challenges, and ways how they can be solved.

As discussed in my first publication: The best way to learn about something, is to engage with that something. And writing publicly is the best way I could think of to engage with that question.

Thank you

If you have come this far, you deserve a big thank you. You've read a lot already and I really appreciate you being part of this. If you liked it, I would really (really) appreciate if you'd share it with a couple of your friends.

Cheers and until next time!

The sidenotes

This section is off topic and contains things I just want to share with you.

I have two sidenotes for you on todays newsletter.

First: I discovered readwise reader last month and I am a huge fan. It stores articles, pdfs, books, videos, etc, which I can highlight directly on the reader. The thing I love most though, is that my annotations and highlights directly sync with my note-taking app, so that whenever I write anything new, I can link it to what I read before (with the annotations I took). They are not paying me to recommend them, but I am so in love with the product that thought you might want to give them a try.

Second: Starting a company has been a dream of mine for many years. And it is a bit weird (but awesome) that I am living that dream now. I posted a video about that feeling on my YouTube channel a couple weeks ago and I wanted to share it here. Maybe you want to take a look at it. I think I especially wanted to highlight to myself that this is a dream I’ve had, because life goes by too quickly to not try to live it mindfully.

Sources

As I mentioned at the beginning: I am not an authority on anything. Before quoting me, review this sources and build yourself an opinion.

The main source of inspiration for this post is Descifrar el futuro, a book by Fedesarrollo. That is where I learned about the Cobb-Douglas relation.

Here are the rest of the sources:

[1] Meet Michel Lotito, the Man Who Ate an Entire Airplane ... or So He Claimed Accessed February 2023.

[2] Beyond GDP. An article by The economist published on April 2013. Accesed February 2023

[3] The power of a single number. I only read the abstract and the first couple pages, which is where I got the quote on the importance of GDP. It is in my reading list, so might talk about it in a future post.

[4] Gross domestic product - Wikipedia. Accessed February 2023.

[5] GDP Per Capita Defined: Applications and Highest Per Country. Accessed February 2023

[6] I used OpenAI's ChatGPT to gain some inspiration for this example. It is similar to the example provided by Crash Course economics video on productivity and growth, so I am quite confident it is right. But reach out if you find a mistake in it.

[7] Growth imperative - Wikipedia. Accessed February 2023

[8] Sustainable development goals. Accessed February 2023

[9] Crash Course’s Economics video “Productivity and Growth” helped a lot in generating this examples. I thought about them myself, but the explanation by Crash Course helped me understand the topic much better. It is a really good video, highly recommended.

[10] Capital (economics) - Wikipedia. Accessed February 2023.

[11] Human Capital - Wikipedia. Accessed February 2023.

[12] Cobb-Douglas Production Function - Wikipedia. Accessed February 2023.

[13] Total factor productivity explained: Cobb-Douglas production function. Accessed February 2023.

[14] Total factor productivity - Wikipedia. Accessed February 2023.

[15] Fedesarrollo - Descifrar el futuro. Editorial Debate. Page 24. 2021 Edition.

Manu, thanks for sharing your thought and opening the conversation. I really enjoyed reading your post and it brought back memories of my econ courses too! The question of why some countries are richer than others has been on my mind for a long time too. There are a few theories out there that try to explain it, but they don't quite cover everything.

One theory is based on geography. Jared Diamond's book "Guns, Germs & Steel" explores how the domestication and nutritional density of plants in a particular area affected the development of society. For example, societies with horses had a higher agricultural productivity than societies located in geographical areas populated by zebras (can be domesticated only one-by-one). Societies living in areas with crops having higher nutritional density had it easier to feed the community and focus on developing tools and weapons (therefore increasing the productivity). On the other hand, communities in areas with lower nutritional value of crops had to focus on feeding themselves, leaving less time for innovation.

Another theory is based on institutional economics, which is explored in the book "Why Nations Fail?" by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson. They argue that a nation's political and economic institutions play a big role in its success or failure. Inclusive institutions that allow everyone to participate in the economy and politics create innovation, productivity, and economic growth, leading to prosperity. In contrast, extractive institutions that benefit only a small group of elites create inequality, hindering innovation, productivity, and economic growth, leading to poverty. There are a lot of examples in the book. For example, the city called Nogales is divided by the boarder - part in Arizona, part in Mexico. This leaves the city for a natural experiment of different institutions (extractive and inclusive) creating different standards of living.

In all of the books authors provide a lot of examples, so I really recommend reading them!

Manu, I really enjoyed reading your Post and am looking forward to reading your further posts on the open questions!

Regarding the questioning of GDP as a measure of a countries well-being and living standards, as well as the factors it does not tell us, I am currently reading the book: “Less is More” by Jason Hickel. It has been incredibly interesting and presented me with a completely new view on the importance of growth and the way our society is built.

I would love to hear what you think of it!!